Lecture 7 Synchronisation And Coordination

Distributed Algorithms

Algorithms that are intended to work in a distributed environment (runs on multiple machines at the same time to solve the problem)

Accomplish tasks such as:

- Communication

- Accessing resources (e.g. replicated data)

- Allocating resources, consensus (agreement on resources etc.)

You achieve synchronisation & coordination through distributed algorithms, and distributed algorithms usually re3quire some sort of synchronisation & coordination!

Timing Models of a Distributed System

- Timing models affected by execution speed, communication delay, clocks and clock drift.

- Most real distributed systems are a hybrid of synchronous/asynchronous

Synchronous Distributed System

Time Variance is bounded

- Bounded execution speed and time

- Communication: bounded transmission delay

- Bounded clock drift

Can rely on timeouts to detect failure (can make assumptions about state of machines given the time)

- Easier to design distributed algorithms

- Very restrictive requirements

- Limit concurrent processes per processor (pre-emption)

Asynchronous Distributed System

Time Variance is not bounded

- Different execution steps can have varying duration

- Communication transmission delays vary widely

- Arbitrary clock drift

Allows no assumption about time intervals

- Can’t rely on timeouts to detect failure

- Most asynchronous problems are hard to solve

- Solution for asynchronous system will also work in synchronous system.

Evaluating Distributed Algorithms

Key properties

- Safety: nothing bad happens

- Liveness: something good eventually happens

General Properties

- Performance (many different metrics: number of messages exchanged, response/wait time, delay/throughput, complexity)

- Throughput =

1 / (delay + executiontime)

- Throughput =

- Efficiency (resource usage: memory, CPU etc.)

- Scalability

- Reliability (number of points of failure)

Synchronisation & Coordination

Doing the right thing (coordination) at the right time (synchronisation)

Coordination

- Coordination Actions:

- What actions will occur?

- Who will perform the actions?

- Agree on Values:

- Agree on global value

- Agree on environment

- Agree on state (is the system in state of error? etc.)

Synchronisation

- Order of all actions:

- Total ordering of events, instructions, communication

- Ordering of access to resources (e.g. mutex)

(Requires some concept of time)

Main Issues

- Time and Clocks

- Global State

- Concurrency Control

Time & Clocks

- Notion of Global Time

- “Absolute” time (conceptually this works, but of course time is relative)

- UTC (Coordinated Universal Time)

- Leap seconds added to atomic time to ensure it still lines up with astronomical time (i.e. still daytime when sun shines!)

- Local Time: not synchronised to a global source

- Clocks in Computers:

- Timestamps to denote the time a certain event occurred

- Synchronisation using clocks:

- perform events at exact times

- Logging of events (can order events by timestamp)

- Tracking (e.g. tracking object with multiple cameras)

make(examine source timestamp vs object timestamp - do we need to recompile? If building on another computer, if clocks aren’t synchronised, may have issues).- Ordering of messages

- Physical Clocks

- Based on actual time

- Ideally

Cp(t) = t, but clocks drift so must regularly synchronise with UTC.- Skew: instantaneous difference

- Drift: rate of change of skew

- Synchronising:

- Internal Synchronisation: only synchronise with each other

- External Synchronisation: clocks synchronise to an external time source (time server: server that has/calculates correct time)

Clock Synchronisation Approaches

Berkeley Algorithm Internal, accuracy 20-25 ms

- Central time daemon - periodically collects time from all nodes, average the result, and then send out a time change to each node to make them in sync

- Sends/receives relative offsets to each nodes (never needs to deal with actual time)

- Generally useful in local area network, or when you don’t need to know what global time is.

- There is no central source of truth, so no notion of global time

Cristian’s Algorithm Has UTC receiver, passive, accuracy 1-10ms (The RTT in LAN)

- Clients periodically request the time

- Clients can’t set the time backwards (it’s usually difficult to deal with events from the future - e.g. timestamps in the future)

- If time server is behind your clock, you slow client clock down until it catches up to time server - this way time doesn’t go backwards!

- Take propagation and interrupt handling delay into account (calculate difference, or take series of measurements and average delay, or use msg with shortest delay)

- Not scalable: centralised server

Network Time Protocol (NTP) Accuracy 1-50 ms

- Hierarchy of servers:

- Primary server has UTC clock

- Secondary server: connects to primary

- …

- Methods

- Multicast (LAN, low accuracy)

- Procedure Call (clients poll)

- Symmetric (between peer servers at same level)

- Synchronisation

- Estimate clock offsets and tx delays between two nodes (retain past estimates, and choose offset estimate for lowest tx delay)

- Also determines unreliable servers

Logical Clocks

Event ordering is more important than physical time:

- Events in a single process are ordered

- Processes need to agree on ordering of causally-related events

Local Ordering

- e -> i e’

- Everything that happens in the same process is causally related

Global Ordering

- Lamport’s global happened before relation ->

- Smallest relation such that:

- e ->i e’ implies e->e’ (i is local)

- For every message, send(m)->recv(m)

- Transitivity: e->e’ and e’->e’’ implies e->e’’

- The relation

->is a partial order:- If a->b, then a causally affects b

- Unordered events are considered to be concurrent (

||)

Implementation

- Software counter locally compute the happened-before relation

- Each process maintains a logical clock

- Process:

- Before timestamping a local event, increment local clock

- Whenever a message is sent between processes:

- Increment local logical clock, and send new value with message

- Receiver takes max of current local clock and received clock, and uses max (increments it)

- Properties:

a->bimpliesL(a) < L(b)L(a) < L(b)does not necessarily implya->b

- Total event ordering:

- Lexicographical ordering

Vector Clocks

- In Lamport local clocks,

L(a) < L(b)does not necessarily implya->b- So can’t deduce causal dependencies from timestamps

- Because clocks advance independently (or via messages) - there is no historic information on where advances come from)

Vector Clocks:

- At each process, maintain a clock for every other process

- Events are timestamped with a vector

Vwhich is a vector of the knowledge about each other clock- i.e.

Vi[j]is i’s knowledge about j’s clock

- i.e.

- Process:

- Initially, V = 0

- Before pi timestamps an event, increment’s it’s own record.

- Whenever a message is sent between processes:

- Process increment’s its clock value and sends entire vector

- Receiver merges the vector with it’s local vector

- Takes the max of each element, and increments it’s own record

Global State

Determining Global Properties:

- Distributed garbage collection: do any references still exist to an object?

- There could be a message in transmission that references the object

- Distributed deadlock detection

- Distributed termination detection: did a set of processes cease activity

- Or are they just waiting for messages?

- Distributed checkpoint: what is a correct state of the system to save?

Consistent Cuts

- Need to combine information from multiple nodes.

- Without global time, how do we know whether local information is consistent?

- Local state sampled at arbitrary points is not consistent: what is the criteria for ‘consistent global state’?

- A cut is a history up to a certain event.

- Consistent Cut: For all events e’, if e->e’, then e is in the cut

- Frontier is the final events in a cut

- A global state is consistent if it corresponds to a consistent cut (a global history is a sequence of consistent global states)

Chandy and Lamport’s Snapshots

Determines a consistent global state, takes care of messages in transit (don’t need to ‘stop the world’). Useful for evaluating stable global properties

Assumptions:

- Reliable communication and failure-free processes

- Point-to-point message delivery is ordered

- Process/channel graph must be strongly connected

- On termination:

- Processes hold their own local state components

- Nodes hold a set of messages in transit during the snapshot

Process:

- One process initiates algorithm by sending a marker message

*(and recording it’s local state - For each node, when it receives

*:- Save local message, and send marker messages to all connections

- Need to store messages up until marker received on that channel

- Local contribution complete after markers received on all incoming channels

Spanner & TrueTime

Global Distributed Database desires:

- External consistency (linearisability)

- Lock-free read transactions (scalability)

External Consistency with Global Clocks

- Data versioned using timestamp

- Read operations performed on a snapshot (provides lock-less reads - faster)

- Write operation has unique timestamp

- Write operations are protected by locks, and get global time during transaction

- Problem: it’s impossible to get perfectly-synchronised clocks (so timestamps could overlap!)

TrueTime

- Add uncertainty to timestamps:

- For every timestamp, there is:

- the value of the time stamp

- Earliest and latest values (these vals are maximum skew from actual time in either direction)

- For every timestamp, there is:

- Add delay to transaction:

- To ensure that timestamps can’t overlap

- Wait until

tt.now(earliest) > s.latest

- Needs to have ‘reasonably synchronised’ clocks

Concurrency Control

- Concurrency in Distributed Systems introduces more challenges on the typical concurrency problems

- No direct shared resources (e.g. memory)

- No global state, no global clock

- No centralised algorithms

- More concurrency

Distributed Mutual Exclusion

Concurrent access to distributed resources - must prevent race conditions during critical regions

- Safety: at most one process can execute critical section at a time

- Liveness: requests to enter/exit critical region eventually succeed

- Ordering: (not critical) requests are processed in happened-before ordering

- Note: Evaluation metrics of Distributed Algorithms (see above)

Central Server 3 messages exchanged, delay: 2 messages, reliability is OK

- Requests to enter/exit critical region are sent to a lock server

- Permission to enter is granted by receiving a token.

- Return token to server when finished critical section

- Easy to implement

- Doesn’t scale well (centralised server overloading)

- Failure: central point of failure (server), or the client with token goes down

Token Ring messages exchanged: varies (if no-one is using it, token just keeps going round), delay=N/2 (max is num nodes), poor reliabilty

- All processes are organised in logical ring

- A token is forwarded along the ring

- Before entering critical section, process has to wait until the token arrives

- Retain the token until left the critical section

- Ring imposes avg delay N/2 (limited scalability)

- Token messages consume bandwidth

- If any node goes down, ring is broken

Multicasts & Logical Clocks Messages exchanged: 2*(N-1), delay 2*(N-1), poor reliable

- Processes maintain Lamport clock and can communicate pairwise

- Three states:

- Released

- Wanted

- Held

- Behaviour:

- If process wants to enter critical section, it multicasts message, and waits until it receives a reply from every process

- If a process is Released, it immediately replies to any request to enter critical section

- If a process is Held, it delays replying until it has left critical section

- If a process is Wanted, it replies to request immediately if the requesting timestamp is jsmaller than it’s own

- If process wants to enter critical section, it multicasts message, and waits until it receives a reply from every process

- Multicast leads to increased overheads

- Susceptible to faults (any node crashing will cause this to fail)

Transactions

An upgraded version of mutual exclusion. Defines a sequence of operations. It is atomic in the presence of multiple clients and failures

- Operation:

BeginTransactionread’s &write’s

EndTransactionCommitorAbort

- “ACID” Properties:

- Atomic: all or nothing (committed in full, or forgotten if aborted)

- Consistent: transaction does not violate system invariants

- Isolated: transactions don’t interfere with each other

- Durable: after a commit, results are permanent (even in presence of failure)

Transaction Classifications

- Flat: sequence of operations satisfying above properties

- simple

- failure: all changes undone

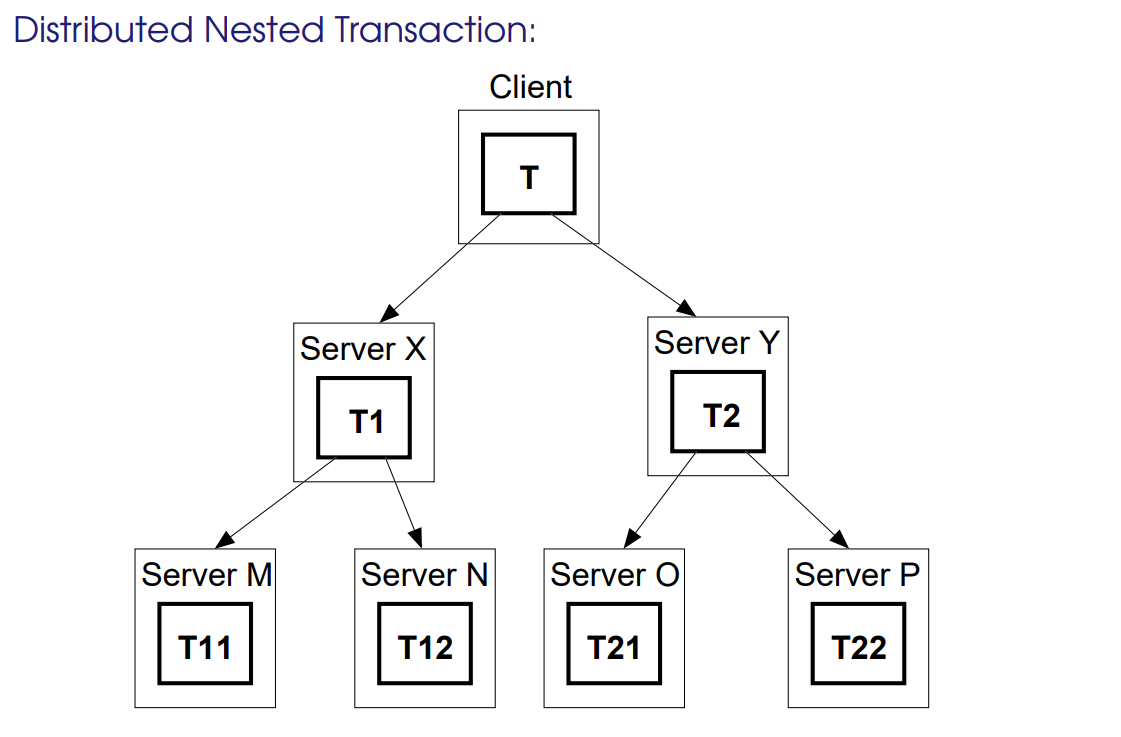

- Nested: Hierarchy

- How to deal with failure? Abort entire, or commit non-aborted parts only?

- Parent transaction may commit, even if some sub-transactions abort

- If a parent aborts, all sub-transactions must abort

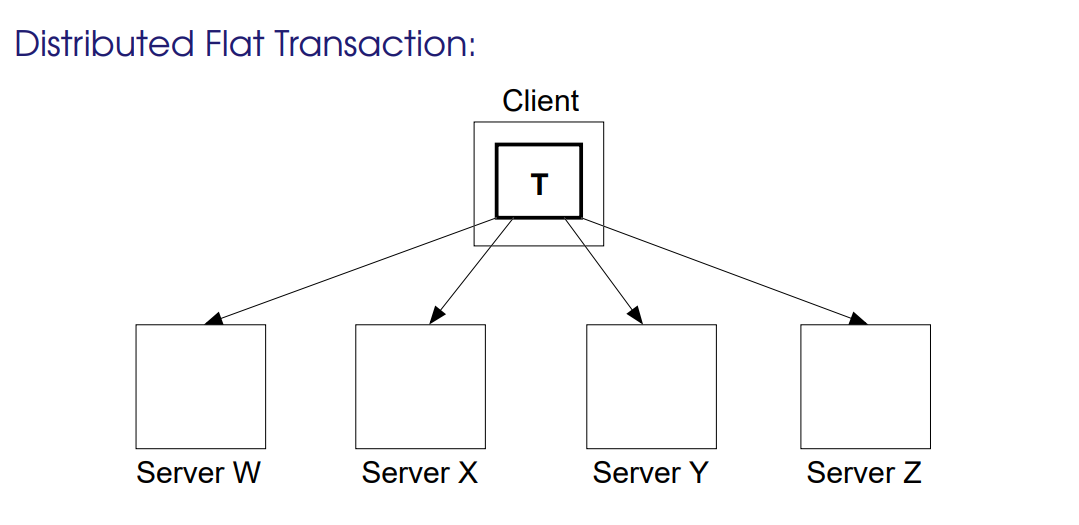

- Distributed: (flat) transaction on a distributed system

Transaction Atomicity Implementation

- Private Workspace:

- Perform tentative operations on a shadow copy.

- Shadow State: easy to abort, but needs more space

- Writeahead log: fast to commit, more expensive to abort

- Concurrency Control (Isolation):

- Simultaneous Transactions may interfere - Consistency and isolation require that there is no interference (otherwise you can get lost update or inconsistent retrieval)

- Conflicts and Serialisability

- Conflict: operations from different transactions that operate on the same data - read-write or write-write conflicts

- Schedule: Total ordering of operations

- A legal (serialisable) schedule is one that can be written as a serial equivalent

- Serial Equivalence

- Conflict operations performed in the same order on all data

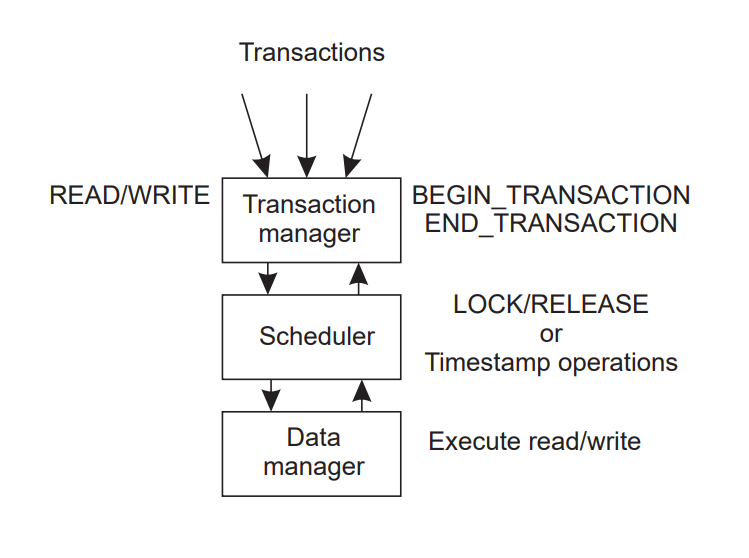

Managing Concurrency

Transaction Manager

Locking Pessimistic approach: prevent illegal schedules

- Basic Lock:

- Locks must be obtained from scheduler before read or write

- Scheduler grants/releases locks, and ensures only serialisable lock obtain is possible

- This doesn’t guarantee serialisable schedule

- Two-phase Locking

- Acquire phase, and then release phase within transaction

- You can only acquire in the acquire stage, and only release int he release stage

- Acquire phase, and then release phase within transaction

- Issues with locking

- Deadlock (detect in scheduler and decide to abort a transaction, or timeout)

- Cascade Aborts

Release(Ti, x) -> Lock(Tj, x) -> Abort(Ti)- Tj will have to abort too because it used

xaferTi! - Dirty read problem: seen value from non-committed transaction

- Solution: strict two-phase locking (release all locks at commit/abort)

Timestamp Ordering Pessimistic

- Each transaction has unique timestamp, and each operation receives the transaction timestamp

- Each data item has two timestamps:

- Read - transaction that most recently read the data item

- Write - committed transaction that most recently wrote to data item

- Also have tentative timestamps (non-committed writes)

- Timestamp ordering rule:

- Write request only valid if timestamp of read >= timestamp of last write

- Read request only valid if timestamp > timestamp of last write

Optimistic Control

- Assume no conflicts occur (detect conflicts at commit time)

- Three phases:

- Working (using shadow copies)

- Validation

- Update

- Validation:

- Need to keep track of read set andw rite set during working phase

- Make sure conflicting operations with overlapping transactions are serialisable:

- Make sure Tv doesn’t read items written by other Ti’s

- Make sure doesn’t write any items read by other Ti’s

- Make sure Tv doesn’t write items written by other Ti’s

- (Either other transactions committed already, or other transactions not committed yet)

- Need to prevent overlapping of validation phases

- Implementations:

- Backward validation

- Check committed overlapping transaction

- Only have to check if Tv read something that Ti has written (read-write only)

- On conflict: have to abort Tv

- Have to keep track of all old write sets

- Forward Validation

- Check non-committed overlapping transactions

- Only have to check if Tv wrote something another Ti has read

- On conflict: abort Tv, abort Ti or wait

- Read sets of non-committed transactions may change during validation!

- Backward validation

Distributed Transactions

- A single transaction will involve several servers (may require several services, and store files on several servers)

- All servers must agree to Commit or Abort

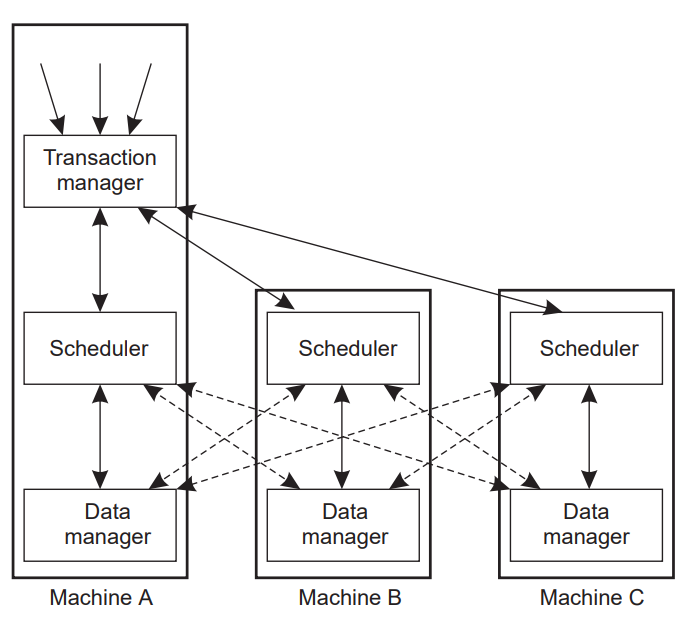

- Transaction management can be centralised or distributed.

Distributed Concurrency Control

- Locking

- Centralised 2PL: single server handles all locks

- Primary 2PL: Each data item is assigned a primary copy

- Scheduler on that server is responsible for locks

- Distributed 2PL:

- Data can be replicated

- Scheduler on each machine responsible for locking own data

- Read lock: contact any replica

- Write lock: contact all replicas

- Distributed Timestamps

- Timestamp assigned by first scheduler accessed (clocks have to be roughly synchronised)

- Distributed Optimistic Control

- Validation operations distributed over servers

- Commitment deadlock (because of mutex on validation)

- Parallel validation protocol

- Make sure that transaction is seralised correctly

Atomicity and Distributed Transactions

- Distributed Transaction Organisation:

- Each distributed transaction has a coordinator (the server handling the initial

BeginTransactionprocedure)- Coordinator maintains a list of workers (other servers involved in the transaction). Each worker must know it’s coordinator

- Coordinator is responsible for ensuring that the whol transaction is atomically committed or aborted (distributed commit protocol)

- Each distributed transaction has a coordinator (the server handling the initial

- Distributed Atomic Commit

- Transaction may only be able to commit when when all workers are ready to commit

- Voting Phase: all workers vote on commit (send

CanCommitmsg to all workers) - Completion phase: all workers commit or abort according to decision (Send either

DoCommitorDoAbortto all workers)

- Voting Phase: all workers vote on commit (send

- Issues:

- Once node has voted yes, it can’t change

- If coordinator crashes, all workers may be blocked

- Could resolve by detecting coordinator crash - talking to other workers to resolve commit

- Transaction may only be able to commit when when all workers are ready to commit

- Two-phase commit of nested transactions

- required in case worker crashes after provisional commit

- On

CanCommitworker: votes no if it has no idea of subtransactions- Otherwise: aborts subtransations of aborted transations, saves provisionally-committed transactions and votes yes.

Elections

When algorithm finished, all processes agree who new coordinator is

- Determining a coordinator:

- Assume all nodes have unique ID

- Election: agree on which non-crashed process has largest ID

- Election Requirements:

- Safety (process either doesn’t know coordinator, or knows the process with largest ID), Liveness (eventually, a process crashes or it knows the coordinator)

- Bully Algorithm

- Message Types:

- Election (announce election e.g. when we notice coordinator crashed)

- Answer (if you don’t get an answer, you are the coordinator)

- Coordinator Announce elected coordinator

- If the highest-numbered process gets an election message, it can immediately respond with coordinator message

- Message Types:

- Ring Algorithm:

- Message Types:

- Election (forward election data)

- Coordinator (announce elected process)

- Every node adds it’s own ID to the election message. When the election message arrives at the starting point, it determines one to be the coordinator, and forwards the coordinator message around ring6

- Message Types:

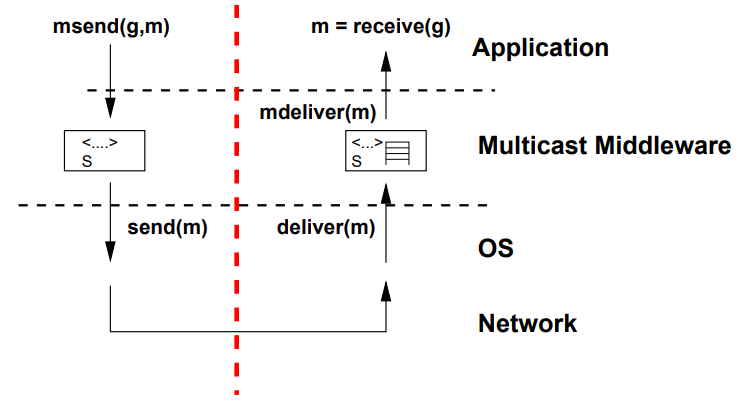

Multicast

- Multicast: single send to a group of receivers

- Group membership is transparent (sender doesn’t need to know who’s in the group)

- Uses:

- Fault Tolerance

- Service Discovery

- Performance

- Event/Notification Propagation

- Properties

- Group Membershp: Static or Dynamic

- Open (all users can send) vs. Closed group

- Reliability

- Communication failure vs. process failure

- Guarantee of delivery (All or none, all non-failed)

- Ordering

- Guarantee of ordered delivery (FIFO, Causal, Total Order)

- Issues:

- Performance

- Bandwidth

- Delay

- Efficiency

- Avoid sending message multiple times (stress)

- Distribution Tree

- Hardware support (e.g. Ethernet broadcast)

- Network vs. Application -level

- Routers understand multicast

- Applications (middleware) send unicast to group members

- Overlay distribution tree

- Performance

Network-level Multicast

“You put packets in at one end, and the network conspires to deliver them to anyone who asks”

~ Dave Clark

- Ethernet Broadcast (send to MAC

FF:FF:FF:FF:FF:FF) - IP Multicast

- Multicast group: class D internet address

- 244.0.0.0 to 239.255.255.255

- Multicast routers:

- Group management: IGMP

- Distribution Tree: PIM

- Have to use the network abstraction: can’t modify the way it operates

Application-level Multicast

- Basic Multicast:

- No reliability or ordering guarantees

B_send(g, m) { for each (p in g) { send (p, m); } } deliver(m) { B_deliver(m); }

- No reliability or ordering guarantees

- FIFO Multicast

- Order maintained per sender

FO_init() { S = 0; // local sequence # for (i = 1 to N) V[i] = 0; // vector of last seen seq #s } FO_send(g, m) { S++; B_send(g, <m,S>); // multicast to everyone } B_deliver(<m,S>) { if (S == V[sender(m)] + 1) { // expecting this msg, so deliver FO_deliver(m); V[sender(m)] = S; } else if (S > V[sender(m)] + 1) { // not expecting this msg, so put in queue for later enqueue(<m,S>); } // check if msgs in queue have become deliverable for each (<m,S> in queue) { if (S == V[sender(m)] + 1) { FO_deliver(m); dequeue(<m,S>); V[sender(m)] = S; } } }

- Order maintained per sender

- Causal Multicast

- Order maintained between causally related sends

CO-init() { // vector of what we’ve delivered already for (i = 1 to N) V[i] = 0; } CO-send(g, m) { V[i]++; B-send(g, <m,V>); } B-deliver(<m,Vj>) { // j = sender(m) enqueue(<m,Vj>); // make sure we’ve delivered everything the message // could depend on wait until Vj[j] == V[j] + 1 and Vj[k] <= V[k] (k!= j) CO-deliver(m); dequeue(<m,Vj>); V[j]++; } - Totally-ordered Multicast

- Every receiver should see messages in the same order

- Sequencer-based approach

- Global sequencer sends a message telling all nodes the sequence number of a message broadcast by another node

- Receivers reorder messages pre processing them

- Agreement-based approach

- Send message to everyone, and then receiver nodes replies with a proposed ordering for the message. Sender then decides which is the best and sends that back to all nodes

- More expensive (increased communications)

- Other implementation options:

- Moving sequencer to distribute load

- Logical clock-based (i.e. lamport clocks) - difficult

- Token-based

- Physical clock ordering

- Hybrid Ordering

- FIFO and Total (since total ordering doesn’t guarantee FIFO ordering)

- Causal and Total

- Dealing with failure in processes and communication